Remote collaboration is nothing new in visual effects, but rarely has it been the predominant way of working—if ever. We spoke with Darren Bell, VFX Producer on TNT’s Snowpiercer, to learn how he managed remote teams from his lakefront cabin on Acton Island.

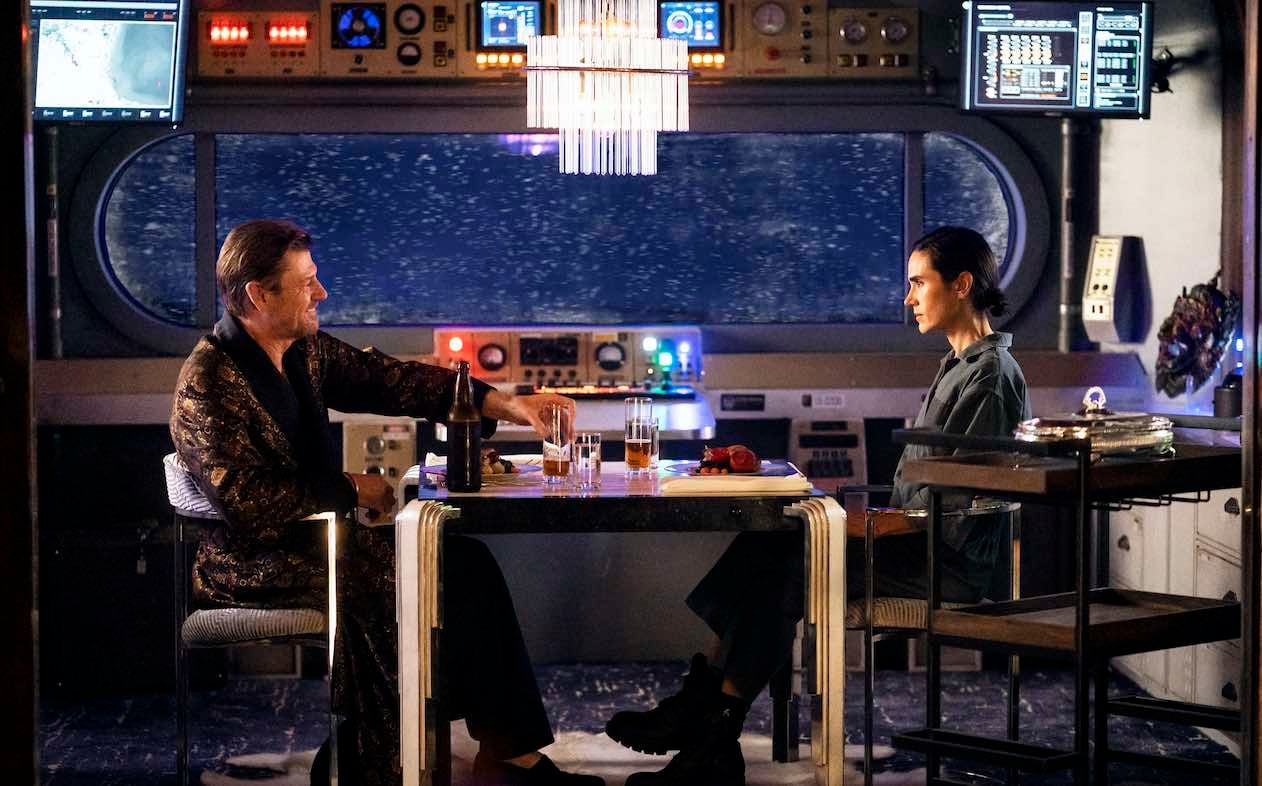

Even COVID-19 could not stop the perpetual train ferrying humanity’s remnants around a frozen post-apocalyptic world. Season 2 of TNT’s Snowpiercer adaptation (based on Bong Joon-ho’s 2013 film of the same name and the 1982 graphic novel Le Transperceneige by Jacques Lob) sees the train’s class struggle truce upended by the surprise return of egomaniacal industrialist Mr. Wilford (Sean Bean), who seeks to take control.

VFX Producer Darren Bell has worked on the Snowpiercer series since its first series, but the second season posed a different challenge: Bell had to perform his duties remotely due to coronavirus lockdown. So for season two, Darren wrangled shots from his lakefront forest cottage on Acton Island, two hours north of Toronto.

“We never saw our client in person; it was all remote work,” begins Bell. “Thankfully, I’ve worked on and off with Snowpiercer‘s VFX supervisor Geoff Scott for the past 12 years. We’re friends and colleagues, so it’s easy for me to trust him and vice versa; all we need is cineSync and a phone call, even if I’m working out by a lake and he’s deep in the city.”

Read on to learn about Darren’s work on Snowpiercer and how remote review and approval tools keep him connected with a talented visual effects team.

Can you please tell us about the VFX in Snowpiercer‘s second season?

The number of visual effects shots went from 1,200 in season 1 to 1,600 in season 2, produced by FuseFX, Mr. X, Image Engine, and Torpedo Pictures.

While season 1 mainly took place inside Snowpiercer, the environmental scope expands in Season 2. For example, Melanie Cavill (Jennifer Connelly) ventures outside to learn whether the Earth’s surface temperature is rising; in episode 206, we see her in the mountains at the research station. In episode 210, Josie Wellstead (Katie McGuinness) goes up onto the train’s roof.

We had some fantastic shots, too, like when the aquarium car explodes at the end of episode 210. There wasn’t a fireball; it’s ice expanding to the point of rapid expansion where metal can’t take it anymore and blows apart. It was fun making the icy tentacle that goes in and envelops all of the turtles and fish. Everything becomes a big icy stew until the metal hits its breaking point.

How do you go about planning for shots and deciding the best approach?

Snowpiercer‘s writers have the freedom to dream up incredible environments and action scenes. Geoff and I will then read the script and work out what’s essential to the story, showrunner, producers, and studio, and decide what to keep to serve the story while keeping things within budget. Often, you can tell the same story with fewer shots; that’s smart editing and storytelling.

All of this is part of the ongoing creative collaboration process. We’re involved in it from project start to project end. We start with storyboards, talk to our vendors, do rough shot-blocking, get signoff and go into animation through to rendering. Remote review and shot approval in cineSync supports us through every stage of this process.

Were any shots difficult to produce from a remote perspective?

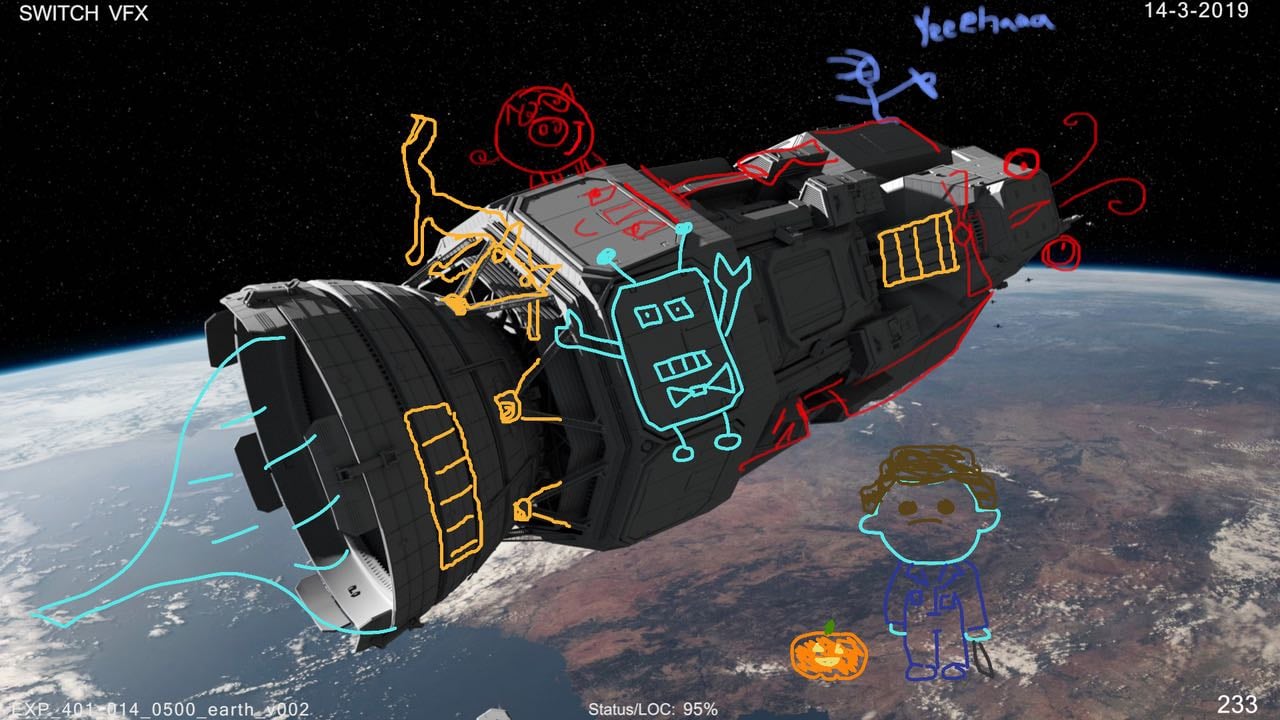

In one shot, a couple of weather balloons go up with cameras on them and reveal the Snowpiercer train wrapped around the Earth from the planet’s outer atmosphere. We had to make sure the train felt defined enough from that perspective and that the audience could see details like light glinting off of the train.

The train is a character in itself, truth be told. We had many more close-up shots of the vehicle in season two, so the team reskinned the asset to improve the rendering detail. We also had to work on things like the speed of the snow kick-up and how it helps viewers gauge how fast the vehicle is moving. In Episode 207, we have a close-up of the whole train turning around in a shot, and it was tough to balance the speed; the back of the train looked like it was going at a different speed than the front because of how far back it goes into the environment. We had to consider all of these things and more.

cineSync was vital across all of these shots. Even when working from home, I could still connect and direct work to the team and ensure the result matched the client’s expectations.

Watch Darren Bell and others discuss the challenges and successes of remote episodic visual effects.

How has your approach to reviewing and approving shots changed since the pandemic?

I’ve used cineSync for 17 years. You can have a client anywhere globally, and you can draw or color-correct onscreen with them in total sync.

When Geoff and I started Season 1 of Snowpiercer, our offices were in the studio in Langley, and our vendors were in Vancouver proper. So we would use cineSync and have ten people sitting in one room looking at a screen talking through a Polycom, and the vendor would do the same thing on their side. Season two was different. When the pandemic hit, we’d have a web of communication instead of doing a direct point-to-point call because those 20 people were all in different places. So things were different but still manageable thanks to cineSync.

The big thing we missed on season two of Snowpiercer, owing to the pandemic, was having editors in the same office as us. On a TV series, you’re usually working with three or four editors in a postproduction office, and at some point during the day, you sit down with them for 10–15 minutes. You get a ton of information, share notes, say what takes to use and which to leave out, and so on. You don’t get those opportunities when you’re not in the same office—but cineSync helps to plug the gap.

Try remote review and approval

Explore cineSync, ftrack Review, and ftrack Studio and discover how they can connect your team.

More from the blog

Enhanced performance in ftrack Studio: Fine-tuning for speed, reliability, and security

Chris McMahon | API, Developer, New features, Product, Productivity, Studio | No Comments

Backlight and the Visual Effects Society forge a partnership for the VES Awards judging process

Kelly Messori | Case Study | No Comments

Presenting the new sidebar: Enhancing project navigation in ftrack Studio

Chris McMahon | New features, Product, Release, Studio | No Comments

Achieving Better Feedback Cycles and Faster Nuke Workflows at D-Facto Motion Studio

Kelly Messori | Case Study, Studio | No Comments

Making the switch: The transition to cineSync 5

Mahey | Announcements, cineSync, News, Product | No Comments

Supporting Your Studio: Free ftrack Studio Training and Office Hours from Backlight

Kelly Messori | News | No Comments

What’s new in cineSync – a deeper iconik integration, laser tool, OTIOZ support, and more

Chris McMahon | cineSync, New features, Product, Release | No Comments